Some people look forward to Easter for the ham, others for the dyed eggs and still others for the cutthroat competition of the egg hunt. Those are all nice. But what I look forward to is a molded white chocolate rabbit. Not the abominable hollow kind, the solid kind. I nibble the ears first, then chew off the feet and after that it’s pretty much a free for all. For something that holds a place of high esteem on my holiday candy calendar, my knowledge of molded chocolate is shallow. It starts and ends at the local candy monger. This year, the anticipation of my upcoming rabbit sparked curiosity. I started wondering about the history of chocolate molds.

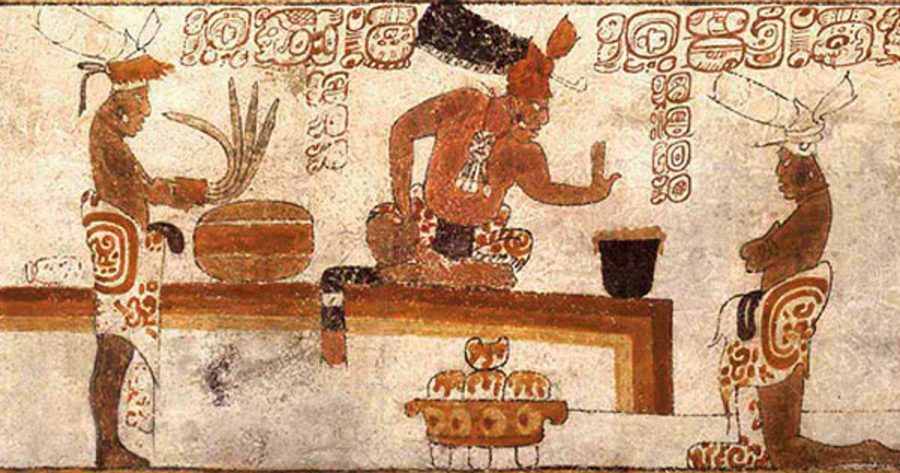

It turns out the first molded chocolate was made in France in the 1830s. The molds, made of copper and coated with silver, produced nuggets that were shaped on the top and flat on the back. You may be wondering why, if chocolate was cultivated by the Mayans as long ago as 5000 BC, it took until 1830 to mold it.

It’s because it was served as a liquid. The Mayans served chocolate as a bitter drink, thought to cure ills and give strength. After chocolate made its way to Spain in the hands of conquistadors, it was treated as a health tonic as well, until someone thought to sweeten it. The more palatable taste led to the opening of chocolate drinking houses across Europe in the 1600s.

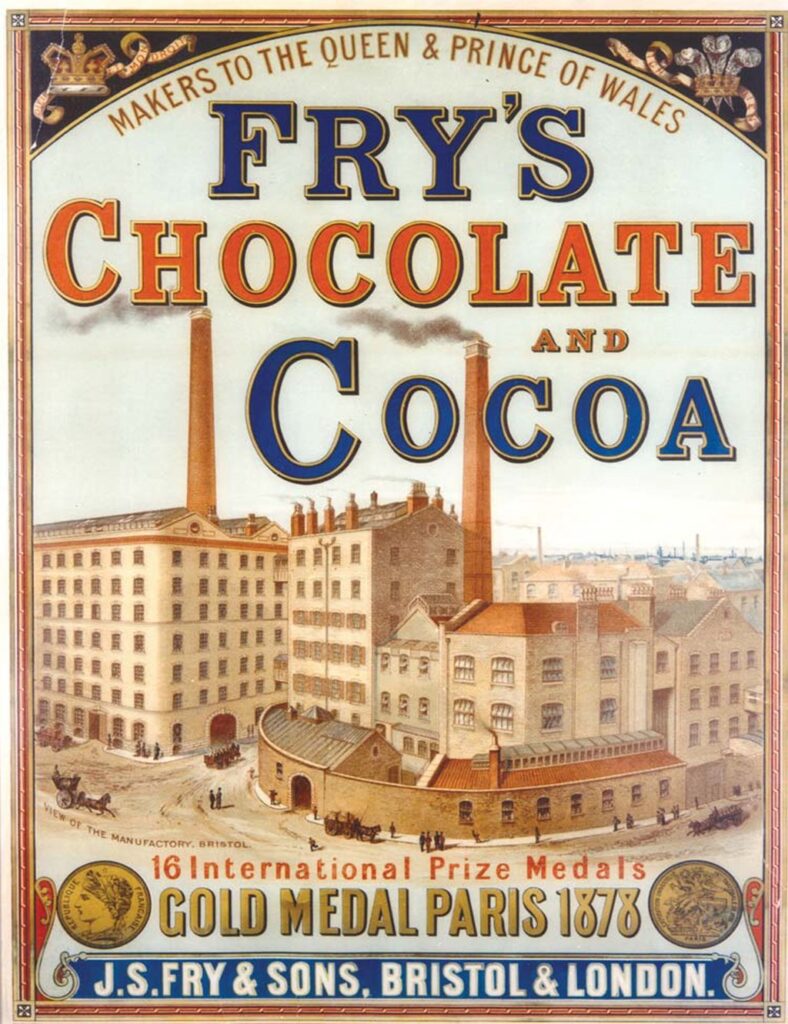

Chocolate did not assume its sold form until the early 1800s. As you eat your chocolate rabbit this year, send kind thoughts to Dutch chemist Coenraad von Houten, who made chocolate less bitter by adding alkaline salts in 1815 and created a press that squished half the cocoa butter out of the liquid in 1828. Thanks to him, the British firm J.S. Fry and Sons was able to figure out how to convert liquid chocolate to a solid that could be molded.

The French expanded upon the original flat backed molded chocolates, developing three-dimensional molds in the 1840s, which were also made of copper and coated with silver. By the 1870s, the copper molds were coated with liquid tin instead of silver because it was cheaper and more durable. Copper did not release the molded chocolate easily, the coatings of silver and tin did.

Germany quickly became the chocolate mold center of the universe. One of the better known makers, Anton Reiche, created over 50,000 different molds during his company’s 90 year run. Reiche began making molds in 1870; his antique molds are prized by chocolate mold collectors.

As mold making evolved, style evolved as well. From 1880-1910, chocolate molds were hyper realistic. From 1910-1930s, molds were became more fanciful and less detailed. Modern molds are utilitarian in comparison, but that’s me injecting my opinion.

What chocolate molds were made of also evolved. Steel replaced copper under the coating of tin around 1910. Lots of materials were tried out to make molds, including bakelite and brass. By the 1940s, nickel-plated steel became the mold material of choice. Plastic replaced metal molds in the 1960s.

Collectors prize antique chocolate molds for their intrinsic beauty. Antique chocolate molds are still used to mold chocolates. They are also used to make chalkware and paper mache figurines. Vaillancourt Folk Art of Sutton, MA is one of the better known commercial makers still using antique molds, but there are lots of small independent makers as well.

Now that you know as much as I do, you can channel thoughts of the historic legacy of chocolate molds while chomping the ears off your rabbit. You are carrying on a tradition that’s over 180 years old. It’s almost an obligation to the ghosts of Coenraad von Houten, Anton Reiche and every chocolate maker and chocolate scientist through the ages. Some history is too delicious not to repeat.

These resources were helpful in writing this post and have way more info than included here:

Easter Egg Chocolate Mold item description from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

A Brief History of Chocolate Molds, from Vaillancourt Folk Art.

History of Chocolate Molds, from Dad’s Follies.

Giving New Life to Vintage Chocolate Molds, from the Institute of Culinary Education.